Decarbonising mining in an era of growing demand for critical metals and minerals

Part one - Original research: Stocktake, barriers and complexities, opportunities, and a way forward.

In this first part of the dss+ Decarbonisation in Mining series, we examine the challenges mining companies face in their decarbonisation journey. From reporting difficulties to implementation barriers, miners have cited various obstacles to educing their carbon footprint. Through research and interviews with 52 mining companies, we have uncovered the primary reasons why decarbonisation has posed challenges for mining companies. We have also compiled several recommendations for how miners can overcome these issues effectively.

Part 2 of this series will provide a more in-depth perspective on how to create an enabling environment for decarbonisation, including adaptation of processes and systems, as well as cultural transformation.

The current rate of decarbonisation is too slow to meet Science-Based Targets

Mining accounts for 4-7% of direct global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.1 However, when scope 3 downstream emissions are included, this rises to 28%, or 19,440 megatons of carbon dioxide equivalent which is second only to agriculture/land use/waste at 30% of global emissions.2

Little is changing, with roughly the same amount being emitted per tonne of mineral output every year.3 This holds especially true for deep gold and platinum mines that are experiencing reduction in ore grades and increasing demand for ventilation and cooling services - technological advances proving insufficient to offset an increase emissions intensity.

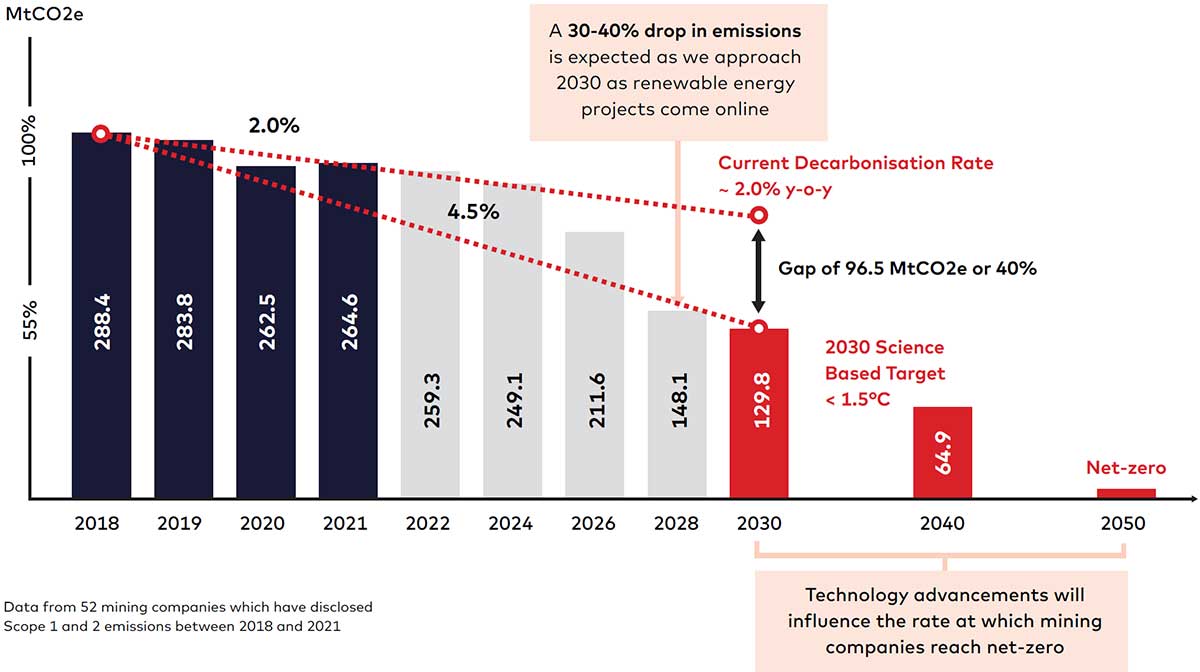

Based on our analysis of 52 mining companies that disclose scope 1 and 2 emissions, we found that the average annual rate of emission reductions was approximately 2% between 2018 and 2021. The current 2% annual reduction rate would result in a 40% gap to 2030 targets as seen in Figure 1. The current decarbonisation rate aligns to a future of more than 2°C of warming, far above the target of 1.5 °C future set out by the Paris Agreement and associated Science-Based Targets (SBTi). To achieve such reductions, the decarbonisation rate must increase to 4.5% per annum across the mining industry and be extended to include scope 3 emissions.

Figure 1: Global mining decarbonisation performance against SBTi (MtCO2e)

1. Globaldata. “Total GHG Emissions of Major Metals and Mining Companies Worldwide by Revenue in 2021”

2. Sustainalytics. ”The Mining Industry: Challenges and Opportuities of Decarbonisation”. 21 November 2022.

3. International Energy Agency. “Critical Minerals Market Review 2023.

Our research showed that where significant emissions reductions have taken place, they tend to be through portfolio optimisation – namely through divestment of coal assets – rather than through operations optimisation or targeted decarbonisation strategies.

This stagnation in emission reductions is increasingly seen as problematic by the investors needed to fund the exploration and expansion of mining operations – 63% of investors would be willing to divest from or avoid investing in a mining operation that does not pursue decarbonisation effectively or that fails to meet its targets.4 Inaction or ineffective action on emissions is increasingly a material risk for miners as they seek greater investment.

of investors would be willing to divest from investing in a mining operation that doesn’t pursue decarbonisation effectively

The challenge with measuring progress against targets

When assessing the mining industry’s progress on decarbonisation, the disparity between companies’ reporting of scope 1 and 2 emissions, and indeed scope 3 emissions, quickly becomes evident.

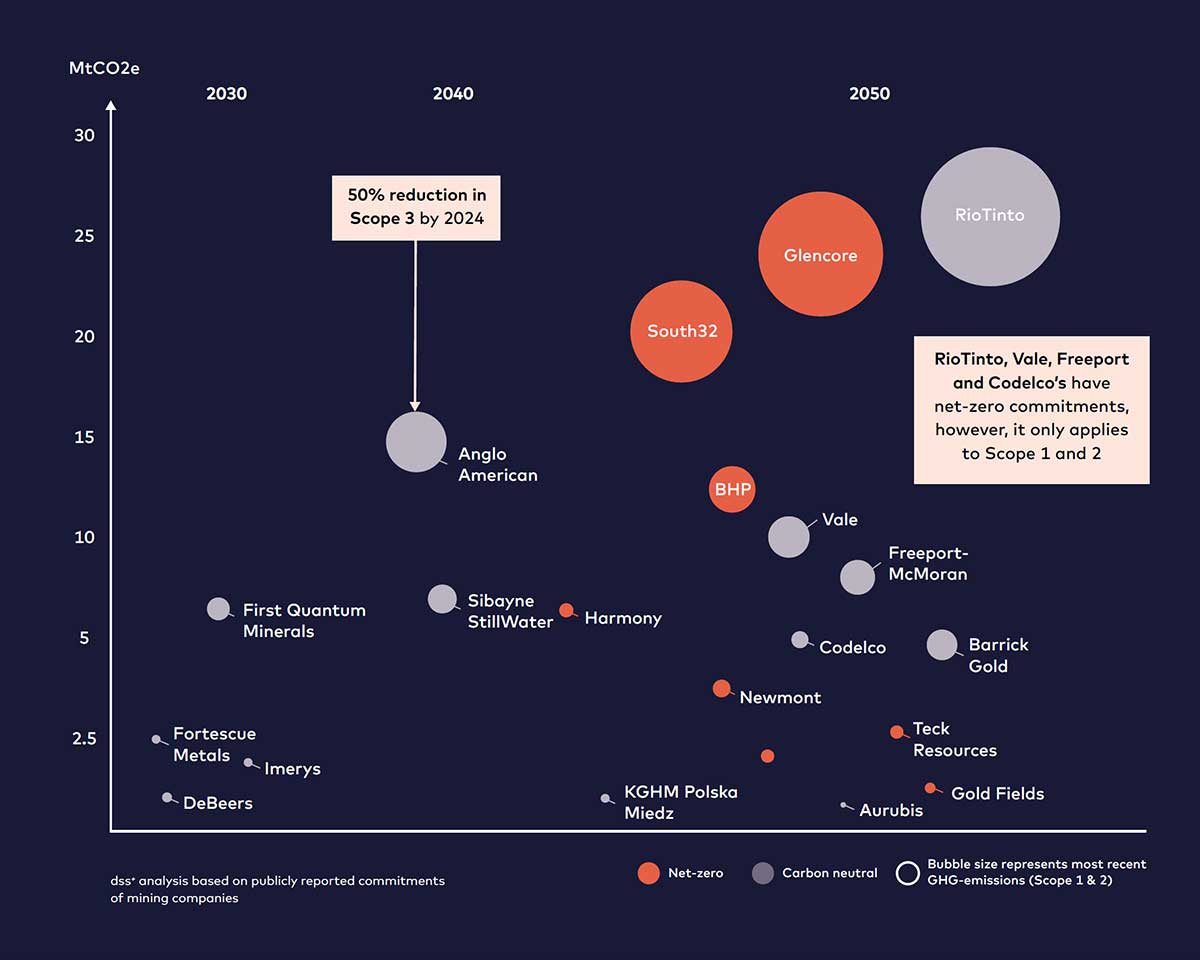

To accurately compare the progress of mining companies, we must first determine whether their commitments pertain solely to Scope 1 and 2 emissions or also include Scope 3. Scope 3 emissions are included, it’s crucial to identify which segments of the miners’ complex supply chains the targets apply to and assess the reliability of available data.

Furthermore, miners tend to use the terms ‘carbon-neutral’ (a less stringent goal focussed on defined emissions) and ‘net zero’ (a more ambitious target comprising all emissions) interchangeably, when the distinction between the two terms can be of crucial importance to lenders and regulators.

Evaluating the mining industry’s progress toward decarbonisation requires considering each company’s impact over time, yet many sustainability reports provide only a snapshot without historical information. It was evident that mining companies worldwide are still struggling to establish consistent methods and data sources to enable effective scope 3 emissions reporting. Figure 2 gives an indication of the quantum of scope 1 and 2 emissions and decarbonisation objectives.

We anticipate that the ICMM guidance on scope 3 emissions reporting, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) requirements, the introduction of ISSB IFRS Scope 1 and Scope 2 disclosure requirements5 and heightened focus from regulatory bodies and investor groups will lead to more precise and standardised definitions. This, in turn, will facilitate easier like-for-like comparisons in the future and help prevent greenwashing by discouraging the use of vague and interchangeable terms.

4. Investing News Network. “ESG Now the ‘Price of Admission’ for Miners as Investors Seek Responsible Companies”. 5 April 2024

5. The ISSB IFRS S1 stands for the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standard 1. It requires entities to disclose information about their sustainabilityrelated risks and opportunities. Specifically, it sets out general requirements for the content, presentation, and timing of sustainability-related financial disclosures.

Sustainability targets of mining majors

Figure 2: Most mining companies’ sustainability commitments focus on Scope 1 and 2 emission reductions, but Scope 3 emissions remain a challenge6

The paradox: mines must increase capacity with urgency, and decarbonise concurrently

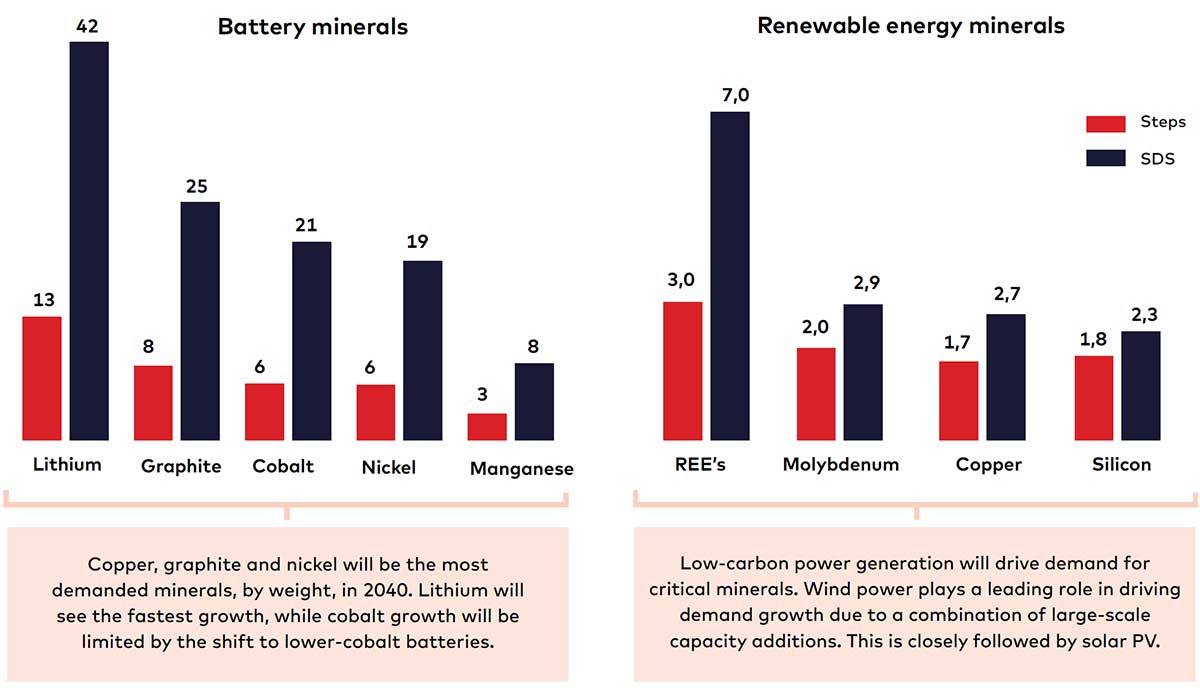

The decarbonisation challenge is further compounded by the need for miners to expand beyond their current capacities to support the energy transition. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), between 2017 and 2022, demand from the energy sector was the primary driver behind a threefold increase in overall demand for lithium, a 70% surge in cobalt demand, and a 40% rise in nickel demand as seen in Figure 3.7 This rapid growth trajectory is expected to persist. Indeed, for cobalt and lithium, existing mines will only be able to produce half the requisite amount by 2030.8 The figure stands at around 80% for copper.9

In the IEA’s Announced Pledges Scenario, critical mineral demand is projected to more than double by 2030. In the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 scenario, it grows three and a half times by 2030, reaching over 30 million tonnes. The IEA emphasises that minerals like copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, and rare earth elements are crucial for a secure and swift transformation of the global energy sector. Mining companies engaged in the extraction and processing of these commodities must urgently expand their capacity to facilitate the future generation, transmission, and storage of renewable energy.

To address the rising demand, companies must substantially expand exploration efforts across diverse geographical regions while simultaneously enhancing the efficiency of their existing assets. This situation presents a paradox: miners must reduce emissions to align with decarbonisation goals and improve their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance, but must ramp up production to meet the unprecedented demand for energy transitions minerals – using more energy and producing more absolute greenhouse gas emissions in the process.

Figure 3: Growth in demand for critical minerals in 2040 relative to 2020 levels – implies 12.2Mt increase

7. International Energy Agency. Critical Minerals Market Review 2023. July 2023.

8. International Energy Agency. The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions. May 2021

9. ibid

Decarbonisation barriers and opportunities

Although many mining companies have committed to decarbonising their operations, our interviews with mining executives across commodities and geographies reveal that several barriers still exist.

The top barriers to decarbonisation, according to mining industry executives, are:

- Inadequate capital management frameworks

- Upfront costs are often extensive

- Lack of operationalisation and centralisation

- Organisational structures that prohibit improvement

- Lack of felt leadership and appropriate mindsets

- Insufficient data and monitoring frameworks

- Skill gaps

- Lack of cohesive and conducive international, national and local policy framework

- Shortage of affordable funding (transition finance)

- No financial incentives

Accelerating decarbonisation in the mining sector through leadership, capabilities and culture

Whilst an immediate focus on practical solutions is showing incremental improvements (as evident in the 2% annual reduction from the analysis) it will still fall short of SBTi. The step change required can only be achieved if leadership adopts a values-based approach and ensures the organisational capabilities drives a sustainable operations imperative.

When leaders demonstrate moving beyond just doing things right to doing the right things this values-based mindset will propagate into the organisation resulting a culture that overcomes these barriers.

Leaders can consider the following to demonstrate their commitment and spur action on decarbonisation:

- Adopt internal carbon pricing aligned to net-zero targets

- Create a cultural context conducive to transformation

- Improve data collection and monitoring

- Improve productivity, reliability and energy efficiency

- Take a long-term view on energy security and supply

- Improved decarbonisation planning

- Co-creation of policy and financing frameworks

- Better quantify value of decarbonisation efforts

Ultimately, there are clear, proven strategies that can help miners to overcome barriers and accelerate their decarbonisation journeys.

Underpinning this is the requirement for a mindset shift within the industry – leaders must recognise the value of reducing emissions, create the appropriate cultural context, build the right organisational and individual capabilities, and develop enabling structures and processes.

In doing so, they can drive significant reductions that are sustainable in the long-term, and thereby support more positive outcomes for all stakeholders.