Process challenges in managing confined space risks

Confined space entries have the potential for high-risk incidents, and small mistakes can result in loss of life. All operations exposed to this risk need to consider how they manage work, and the associated risk, in a robust manner. But how should organisations manage the common challenges to ensuring the correct risk procedures when managing confined space entries?

Confined Space Entry is synonymous with serious injuries and fatalities in various industries, both historically and today. What are some common challenges that organisations in production environments face in managing the high risk of confined space entries?

From observations in industries such as in mining and metals refining, there are a few aspects for organisations to consider to reduce their residual risk exposure.

For those not familiar with confined space entry, there are 2 broad types – standard and permit-required confined spaces.

A Confined Space is:

- A space that is large enough and so configured that a person/employee can enter it

- A space that is not designed for continuous human occupation

- A space that has limited or restricted entry or exit

A Permit-Required Confined Space, on the other hand:

- Contains or has potential to contain a hazardous atmosphere

- Contains or has potential to contain a material with the potential for engulfment or entrapment

- Has an internal configuration with potential for entrapment due to internally converging walls, a downward sloping floor or tapering to a smaller cross-section

- Contains any other recognised serious safety or health hazards.

The risks at play with regards to confined space entry include entrapment, inundation, drowning or exposure to hazardous materials (thermal, toxic, oxygen rich or oxygen deficient).

Confined space entry is not a new activity and has been a common aspect of work in process plants, refineries (oil, gas, and metal) as well as in logistics and distribution operations. Even a local coffee roastery may have a fire water tank that needs an internal inspection every so often.

The scope of possible work in confined space entry conditions is vast, and it is commonplace for large plants to plan for this work under shutdown conditions.

The deferment of confined space work to a single month of the year (or less) is a double-edged sword: this non-regular work routine ensures that there is adequate planning and that work is not done during normal operation, but the infrequency of work and shutdown time pressures also limit the amount of close attention each job can get.

As such, a single slip-up can result in a serious incident – so the margin for error is low compared to more commonly executed tasks.

Below are three aspects that are important to consider when ensuring that confined-space entry risks can be adequately addressed.

1. The Overlap of Business Assurance Processes

Any business that operates a production type environment has layers of complexity in the management of the business and of work. Such businesses will have multiple processes to control work at the frontline. It is imperative that organisations understand the scope and intent of each process if they wish to understand how risks can be managed.

In a typical production business (for example, a metal refinery) there are three key processes of concern:

- How to plan what work is to be done (Work Planning)

- How to identify and manage the risks from that work (Risk Management)

- How to manage the execution of work (Permit to Work).

These three systems are not often centralised in a single business function; work is managed through planning, risk is managed through safety and permitting is left to the frontline supervisor. Whilst it is right to have specific qualified functions dealing with each of these assurance cycles, it is vital that they communicate. Without doing so, three well-designed processes are run in isolation with little cognisance of the limitations in the processes.

2. Risk Management Bureaucracy

Most businesses have a risk management system, and some are more effective than others. In many cases, incidents have driven the implementation and improvement of risk management systems. In any case, most production environments are legislated to have a risk management system and this is normally “owned” by the safety department.

While it is commonplace to centralise risk management expertise into the risk or safety departments, the real issue is operational (production and engineering) accountability. Safety is a line management responsibility and must be driven by the line-organisation, with the framework and expertise is provided by the safety or risk function/s. The single biggest issue with making risk management useful is integrating processes, documents and expertise from the safety or risk office into the line-organisation.

The integration of risk management documents, such as baseline, task or contractor risk assessments and the criteria for critical controls is one aspect of the challenge, but another is the very design of the various layers of the risk management framework. An indicative risk management framework (with hierarchies):

A sound risk management framework ensures that each layer in the organisation has a role to play, but many organisations get tripped up in making the cascade of this process too complex.

Everyone should play a role, but the fundamental requirement for risk assessments and control criteria and checks, should be easily used in the field, from frontline to management levels.

3. Controlling Work at the Frontline Through Permits

The permit-to-work process is central to the prevention of fatalities. All organizations that undertake work such as confined space entry should have a mature permit-to-work system in place.

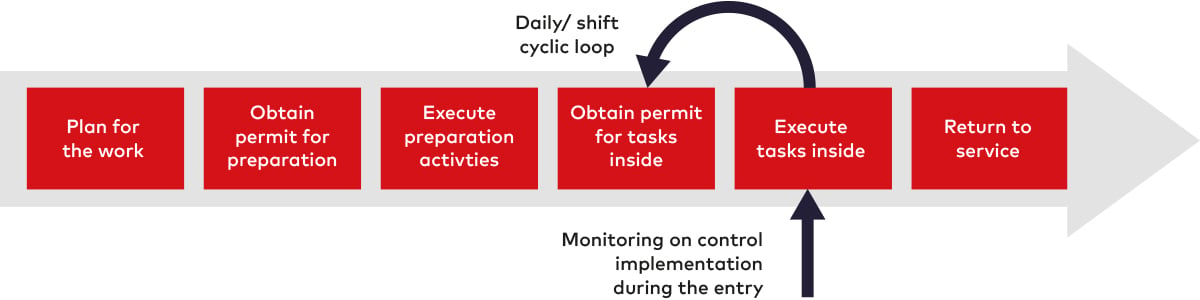

For a confined space entry, permit requirements for work inside the confined space are often necessitated by another permit for the preparation activities. As such, in order to perform safe work inside, you need to plan for and execute quality work beforehand.

An indicative Permit-To-Work process flow:

The Permit-to-Work plays the role of controlling work execution and ensuring that critical controls are in place before work starts. The process and linked documents should be robust enough to address all critical controls that may feature for any work performed on the site.

|

A note on permits It is best practice to have specific permits for different types of work, such as hot work, cold work and confined space entry. This is to ensure that the checks and balances for each type of work is done correctly and that the correct levels of approval are sought. It is also important to ensure that permits are developed succinctly and with clear objectives in mind. Permits are often developed based on historic templates with haphazard additions over time. As such, many organisations do not cross-check their permits against the latest critical controls in the risk management process to ensure that the permit checks for the successful execution of other processes. A good permit is one with clear and logical structuring, but a detailed discussion with the job executors. A joint field visit between issuer and receiver, for example, is a good practice to follow. |

In Conclusion

Confined space entries have the potential for fatal incidents, and small mistakes can result in loss of life. All operations exposed to this risk should consider the management of work processes in relation to the risks at hand to prevent serious confined-space incidents.

Overcoming the common mistakes in the execution of these processes is necessary to ensure they are sufficiently robust. However, it is critical that the integration of these processes is assessed and challenged to ensure that when a worker enters a confined space, they can be sure that they are going home that evening.